Part I: The Spark in the Garden – Forging a Dream

Professional wrestling is a spectacle built on larger-than-life physiques and Herculean archetypes. Few figures are as improbable as Mick Foley in its annals. He is also profoundly human. His story is not one of genetic superiority. It is not of predestined greatness either. Instead, it is about a quiet, suburban fan. Through sheer will, artistic sensibility, and an astonishing capacity for pain, he entered the very narrative he so adored. He achieved this remarkable feat through sheer willpower. To understand the man behind Cactus Jack, Mankind, and Dude Love, you must first learn about the boy. He grew up in Long Island. His entire life was set on a new course by a single, transcendent moment of performance art.

An Idyllic, Unlikely Beginning

Michael Francis Foley was born on June 7, 1965, in Bloomington, Indiana. He spent his formative years in the Long Island town of East Setauket, New York. His upbringing was steeped in athletics and academia. His father, Jack, was a high school athletic director with a doctorate. His mother, Beverly, was a physical education teacher. This environment provided a stable, almost conventional, backdrop for a young man who would choose a most unconventional path. At Ward Melville High School, Foley was an active, if not exceptional, athlete, participating in lacrosse and amateur wrestling. Among his wrestling teammates was a young Kevin James, the future actor and comedian. This biographical footnote grounds Foley’s origins in a relatable suburban reality. It starkly contrasts with the brutal and surreal world he would later inhabit.

Friends from his youth recall a boy who was quiet in public. In his own circle, he was a prankster and a “funny guy.” This duality—the reserved observer and the charismatic performer—would become a hallmark of his professional career. Yet, beneath the surface of this idyllic childhood, a deep and abiding passion was taking root. Foley was a voracious consumer of professional wrestling, watching any program he could find, often late into the night. He was captivated by the larger-than-life characters, but one, in particular, captured his imagination: the high-flying, primal “Superfly” Jimmy Snuka.

The Epiphany at Madison Square Garden

The singular event that transformed Foley from a passive fan into an aspiring performer occurred in October 1983. Foley was a freshman at the State University of New York at Cortland. He made a pilgrimage, hitchhiking over 200 miles to the mecca of professional wrestling, Madison Square Garden. He paid more than face value for a ticket. His hero, Jimmy Snuka, faced the villainous “Magnificent” Don Muraco in a steel cage match. Foley secured a seat near the front. Footage from that night clearly shows the enraptured college student in the crowd.

The match was brutal, but it was its climax that provided Foley’s epiphany. Snuka ascended to the very top of the 15-foot-high steel cage. In a breathtaking leap of faith, he delivered his signature “Superfly Splash” onto the prone Muraco below. For Foley, this was more than a wrestling move; it was a moment of pure, unadulterated emotional theater. He later recalled the feeling in the arena. He remembered how the entire crowd, himself included, had “goosebumps and tears in their eyes.” It was an act of physical courage that created a powerful, collective emotional experience. In that moment, Foley’s ambition crystallized. He didn’t just want to be a wrestler. He wanted to be the person who could move people like that. He aimed to create moments that transcended the scripted violence. These moments touched something deeper in the audience.

This experience serves as the Rosetta Stone for Foley’s entire career. He was, first and foremost, a fan. His motivations began with a desire to replicate the profound emotional impact wrestling had on him. He also wanted to respond to that impact as a spectator. His character creations and his most iconic performances also stemmed from this desire. He was not just a performer starting a business. He was an artist. His main aim was to make the audience feel what he felt that night at the Garden. This fan-centric perspective explains his unparalleled connection with the audience. It highlights his deep empathy. It also shows his willingness to sacrifice his own body—not for championships or glory. He did it for the sake of creating an unforgettable moment for his fellow fans.

From Backyard to Training School

Foley’s newfound calling first manifested in the ultimate fan expression: backyard wrestling. He began filming staged matches with his friends. In these homemade tapes, he developed his first proto-persona. It was a groovy, charismatic character named “Dude Love”. A teenage Foley demonstrated a natural ability in these amateur productions. His uncanny talent to deliver compelling interviews, or “promos,” hinted at the master orator he would become.

His passion did not go unnoticed. A wrestling promoter independently discovered some of Foley’s tapes and was impressed by his raw talent. The promoter put him in touch with the veteran wrestler and renowned trainer, Dominic DeNucci. This was Foley’s entry into the professional world, and his dedication was immediately put to the test. While still a full-time college student, Foley would make the arduous 400-mile, four-hour drive every weekend. He traveled from Cortland, New York, to DeNucci’s school in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to train or wrestle. This extraordinary commitment led him to sacrifice a typical college social life. He chose grueling training sessions instead. This set the pattern of sacrifice that would define his career.

In DeNucci’s school, he trained alongside future wrestling personalities. These included referee Brian Hildebrand (Mark Curtis) and a young Shane Douglas. Upon first seeing Foley’s less-than-imposing physique, Douglas admitted he thought Foley “would be done by day one”. It was a sentiment Foley would encounter for years to come, and one he would consistently, and painfully, prove wrong.

Part II: Paying Dues in Blood and Sweatsocks – The Rise of Cactus Jack

Mick Foley’s entry into the professional wrestling landscape was a baptism by fire. It was a grueling apprenticeship. He traveled the backroads of the sport, honing his craft in dimly lit arenas for meager pay. It was during this period that he forged his foundational persona, Cactus Jack. He discovered a unique, brutal currency. This currency allowed him to thrive in a world of giants and bodybuilders. It was an unparalleled willingness to endure and weaponize pain.

The Jobber and the Journeyman

Foley made his professional debut on June 23, 1986. He wrestled under the name “Cactus Jack Manson.” This moniker combined an homage to his father, Jack, with a nod to the infamous cult leader Charles Manson. The name helped cultivate an unpredictable outlaw image. In his second-ever match, he wrestled for the then-World Wrestling Federation (WWF). He served as a “jobber,” or enhancement talent. His role was to lose to more established stars. Teaming with Les Thornton, he faced the formidable British Bulldogs. A single, notoriously stiff clothesline from Dynamite Kid dislocated Foley’s jaw. It left him unable to eat solid food for weeks. It was a harsh introduction to the physical realities of the business.

Foley displayed a keen awareness of the industry’s political landscape even at this early stage. He soon quit his WWF jobber run. He feared he would be permanently typecast as a perennial loser. He worried his career would stall before it began. He instead embarked on the traditional journeyman’s path, working in various independent and regional territories across the country. He traveled to the Continental Wrestling Association (CWA) in Memphis. In World Class Championship Wrestling (WCCW) in Texas, he further developed the Cactus Jack character. He won several regional tag team and light heavyweight championships. This was the wrestler’s equivalent of “paying dues.” He slept in his car and fought for as little as ten dollars a night. It was a stark contrast to the polished developmental systems of the modern era.

World Championship Wrestling (WCW) – The Glass Ceiling

In 1989, Foley’s relentless work ethic earned him a contract with the nationally televised World Championship Wrestling (WCW). He made an immediate impression on management. He punctuated his debut match loss with a dangerous elbow drop from the ring apron to the unforgiving concrete floor. This move would become a signature of his high-risk style. In WCW, he was cast as a villain, or “heel.” However, his incredible, death-defying bumps and raw intensity earned him a growing following. Fans began to cheer for him despite his villainous alignment. His feuds with top WCW stars like Sting cemented his reputation as a credible and exciting performer. A Falls Count Anywhere match against Sting at the 1992 Beach Blast pay-per-view was a wild and chaotic brawl. It spilled all over the arena. Foley himself long considered this bout his best work.

The turning point of his WCW career, and perhaps his entire life, was his legendary feud with Big Van Vader. This feud, with the monstrous and brutally physical Vader, occurred in 1993 and 1994. Vader was known for his “stiff” style. His punches and moves were delivered with legitimate force. Because of this, many wrestlers feared working with him due to the high risk of injury. Foley, however, saw an opportunity. He willingly entered a program with Vader, knowing the resulting matches would be unforgettable in their realism and violence. The feud produced some of WCW’s most brutal moments. In one infamous match, Vader powerbombed Cactus Jack onto the exposed concrete floor outside the ring. This caused a legitimate concussion and temporary loss of sensation in Foley’s left foot.

Following this legitimate injury, WCW creative devised a storyline that Foley found deeply insulting. The story stated that Cactus Jack developed amnesia. He was institutionalized and then escaped. The angle was widely panned by critics and fans. It earned the Wrestling Observer Newsletter‘s “Most Disgusting Promotional Tactic” award for 1993. This highlighted the creative frustrations Foley often felt. Management didn’t seem to understand the source of his appeal.

The feud with Vader culminated in one of the most infamous legitimate injuries in modern wrestling history. On March 16, 1994, during a WCW tour in Munich, Germany, Foley attempted a “hangman” spot, a move where his head gets caught between the top two ring ropes. The ropes, however, had been tightened to an extreme degree. As Foley struggled to free himself, he tore two-thirds of his right ear. Moments later, as the match continued, Vader grabbed Foley’s head and ripped the damaged ear completely off his skull. In a surreal moment, the referee calmly picked the ear up from the mat as the two men continued to wrestle.

This incident crystalized Foley’s relationship with pain and his growing dissatisfaction with WCW. He was not upset about the gruesome injury itself. He was profoundly frustrated by WCW management’s actions. Booker Eric Bischoff, in particular, refused to capitalize on the raw, authentic drama of the moment. They were hesitant to incorporate the real-life ear loss into a storyline. This hesitation baffled Foley. It was a major factor in his choice to leave the company in 1994.

For Mick Foley in his early career, pain was not merely an occupational hazard. It was his primary currency. It also served as his most effective marketing tool. In an industry dominated by chiseled physiques and towering frames, Foley did not fit the mold. He understood that he could not compete on aesthetics. Therefore, he identified a market inefficiency in the spectacle of wrestling: the threshold for authentic-looking suffering. He consciously used high-risk maneuvers and took brutal punishment to differentiate himself, forcing promoters and fans to take notice. The Vader feud was the apex of this strategy. He knew that the resulting matches would be uncomfortably real and thus unforgettable. The ear incident, while accidental, became the ultimate symbol of his “hardcore” credibility. His frustration with WCW’s handling of it shows he saw his own physical destruction as a narrative opportunity. He understood that in the theater of wrestling, genuine suffering was an immensely powerful storytelling device. He destroyed his body to build the “Cactus Jack” brand. He made it synonymous with a level of danger and realism. Other performers could not, or would not, match this level.

Part III: The King of the Deathmatch and the Anti-Hardcore Messiah

Mick Foley left the creative confines of WCW. He embarked on a journey to two epicenters of wrestling’s most violent subgenre. These included the “deathmatch” rings of Japan and the blood-and-guts crucible of Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW). In these two promotions, he would reach the zenith of his hardcore persona. Then, he deconstructed it in a display of psychological and performative genius. This proved he was far more than a mere stuntman.

IWA Japan: The King of the Deathmatch (1995)

In 1995, Foley traveled to Japan to compete for the International Wrestling Association (IWA). This promotion specialized in the “deathmatch.” It is a form of wrestling that eschews traditional rules in favor of extreme violence and outlandish weaponry. There, he entered the now-infamous “King of the Deathmatch” tournament. It was a brutal one-night ordeal. It has achieved mythical status among hardcore wrestling fans. The tournament featured an international lineup of extreme competitors. They engaged in no-holds-barred bouts involving baseball bats wrapped in barbed wire and beds of nails. The final included C4 explosives.

By the time Cactus Jack reached the final, he had already endured savage beatings and lacerations from barbed wire, thumbtacks, and nails. His opponent in the final was his mentor and fellow hardcore icon, Terry Funk. Their match was a “No Rope, Barbed Wire, Exploding C4 and Time Bomb Deathmatch” held in the open air of Kawasaki Baseball Stadium. The bout was a symphony of destruction that left Foley with third-degree burns and over 50 stitches. Despite the carnage, Foley has referred to his work in Japan with pride, stating that he and Funk “revolutionized hardcore wrestling”. In a fascinating glimpse into his artistic process, Foley revealed that he was “highly motivated” for one of his barbed wire matches against Funk by listening to the music of singer-songwriter Tori Amos, with the goal of having the “best Barbed Wire Match of all time”. This juxtaposition of brutal violence and artistic inspiration reveals the complex mind behind the mayhem. He had reached the physical apex of the hardcore style, earning the crown of “King of the Deathmatch”.

Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW): The Thinker in a Violent Land

Upon his return to the United States, Foley found a natural home in Paul Heyman’s Philadelphia-based Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW). The promotion’s renegade spirit and violent, anti-establishment style were perfectly suited for the Cactus Jack persona. He had memorable feuds with ECW mainstays like Sabu, Tommy Dreamer, and The Sandman. These rivalries further cemented his reputation as a hardcore legend.

However, Foley’s relationship with the notoriously bloodthirsty ECW fanbase began to sour in 1995. Two incidents deeply disturbed him. The first was seeing a fan-made sign in the crowd. It read “Cane Dewey,” a crude reference to his real-life, three-year-old son, Dewey. The second came at the Wrestlepalooza event. Wrestler J.T. Smith suffered a severe and legitimate concussion after a botched dive onto concrete. The audience responded with callous chants of “You fucked up!”. These moments were filled with cruelty. The line between fantasy violence and real-life consequences was so callously disregarded by the audience. This angered Foley.

In response, he executed one of the most intellectually brilliant heel turns in wrestling history. He began a series of scathing, articulate promos. They were not aimed at his opponents. Instead, they targeted the ECW fans themselves. He renounced his status as a hardcore icon. He decried the fans for their bloodlust. He praised the more mainstream, “sports-entertainment” oriented WWF and WCW. To further antagonize the crowd, he deliberately began wrestling a slow, methodical, technical style. He deprived them of the violence they craved. Many, including Foley himself, consider this period to be his finest work on the microphone. He had weaponized his intellect. He proved he could manipulate and enrage an audience with words. It was as effective as with a weapon.

This period in ECW marked the birth of Foley as a “meta-performer.” His character directly commented on the performance itself. It also addressed the audience consuming it and the wrestling genre as a whole. Standard wrestling operates within the fictional world of “kayfabe.” The “Cane Dewey” sign was a moment where the real world intruded upon that fiction. Foley’s family was involved, and he found this intrusion repugnant. His response was to create a character whose motivations were now explicitly about the audience’s reaction. Cactus Jack was no longer just a wild brawler. He became a performer who was acutely aware of his audience’s nature. He was disgusted by their bloodthirsty tendencies. His “anti-hardcore” promos were the epitome of this meta-commentary. He was performing a critique of his own performance genre, live, in front of the very people he was critiquing. This is a level of performance art rarely seen in any medium, let alone professional wrestling. This intellectual layer was first honed in the bingo hall arenas of ECW. It would become the bedrock for the psychological complexity of Mankind. It also underpinned the entire “Three Faces of Foley” saga in the WWF.

His final ECW match was against Mikey Whipwreck in March 1996. The ECW fans knew he was leaving for the WWF. They set aside their kayfabe hatred. They gave him a thunderous standing ovation and chanted “Please don’t go!”. After the match, a visibly moved Foley addressed the crowd. He told them their reaction made his entire brutal journey worthwhile. He has since called this moment of mutual, earned respect his favorite in his entire wrestling career.

Part IV: The Three Faces of Foley – A Study in Character Psychology

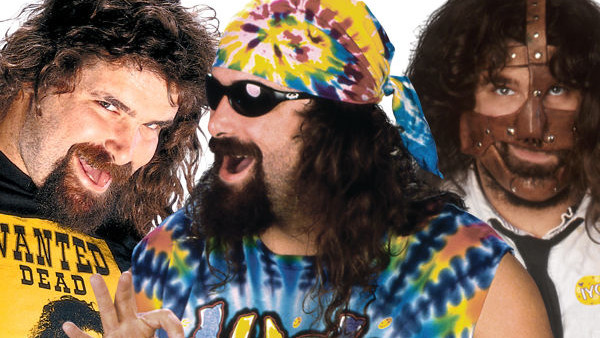

Mick Foley arrived in the World Wrestling Federation in 1996. He brought with him more than just a reputation for absorbing punishment. He introduced a creative and psychological depth that would forever change the landscape of character development in wrestling. Over the next two years, he would unveil three distinct personas. These personas were Mankind, Dude Love, and the returning Cactus Jack. Known collectively as the “Three Faces of Foley,” it was more than a versatile gimmick. It was a long-form narrative about a fractured psyche. It portrayed a public performance of identity crisis and, ultimately, integration.

Mankind: The Tortured Soul

Vince McMahon, the WWF chairman, showed little interest in the established Cactus Jack character upon Foley’s arrival. He felt it was too niche and violent for his audience. The creative team’s initial pitch was for a character named “Mason the Mutilator.” Foley immediately recognized this name as a potential career “death knell.” In a crucial act of creative agency, Foley pitched an alternative: “Mankind.” He explained to McMahon the name’s powerful double meaning. He could speak of the “destruction of Mankind.” This referred to both himself as a wrestler and, in a larger sense, the entire human condition. McMahon agreed.

The initial incarnation of Mankind was a terrifying and enigmatic figure, a “deranged miscreant who lurked in boiler rooms”. He wore a brown, tattered tunic and a menacing, Hannibal Lecter-esque leather mask that obscured his famous face. He spoke in a pained, distorted voice, rocked back and forth, and had a disturbing habit of pulling out his own hair during moments of agitation. His signature finishing move, the “Mandible Claw,” involved shoving his fingers down an opponent’s throat. Foley himself invented a tragic backstory for the move, envisioning Mankind as a tormented concert pianist who had smashed his own fingers with a hammer, rendering him unable to create music.

Foley’s inspirations for the character were deeply literary and artistic. He drew from Mary Shelley’s classic novel Frankenstein. He saw Mankind as a misunderstood monster. He also drew inspiration from the tortured, emotional music of Tori Amos. The character’s eerie, gentle piano exit theme was inspired by a scene in The Silence of the Lambs. Foley imagined Hannibal Lecter feeling a “peace of mind” after committing horrific acts of violence. This sophisticated thought process elevated Mankind beyond a simple monster-of-the-week into a figure of genuine psychological complexity.

Academic analysis of the Mankind character suggests it was a nuanced performance of mental illness. Foley’s portrayal was imbued with a profound sense of pathos. Ringside commentary often relied on stigmatizing language like “deranged” and “lunatic.” However, his portrayal conveyed vulnerability. The character exaggerated the inherent trauma of being human. This exaggeration made him, paradoxically, one of the most relatable figures on the roster. A series of groundbreaking, confessional-style interviews with commentator Jim Ross, set in dark boiler rooms, provided context for Mankind’s pain. In these segments, Foley broke the fourth wall of kayfabe. He discussed his real-life struggles and insecurities. This humanized the monster and challenged the hyper-masculine norms of professional wrestling. It allowed a top male star to express deep-seated vulnerability and trauma.

Dude Love: The Childhood Dream

In 1997, the WWF unveiled the second face of Foley: Dude Love. This character was the polar opposite of the tormented Mankind. He was a groovy, tie-dyed, fun-loving hippie. A “cool cat,” he danced his way to the ring. He spoke of peace and love. Dude Love’s origin was deeply personal. Foley created this character as a teenager in his backyard wrestling videos. It embodied the charismatic, confident “ladies’ man” he dreamed of being.

The character was introduced to the WWF audience. This introduction happened through the same series of revelatory sit-down interviews with Jim Ross. These interviews had fleshed out Mankind’s backstory. Dude Love made his official debut on the July 14, 1997, episode of Raw. He appeared as “Stone Cold” Steve Austin’s surprise tag team partner. The moment was pure comedic brilliance. Austin’s bewildered and disgusted reaction to his new dancing partner created an instant classic moment. It showcased Foley’s incredible performance range. Psychologically, Dude Love represented Foley’s unrepressed, joyful id. He was the fantasy and the wish-fulfillment. He provided a necessary and stark contrast to the pain of Cactus Jack and the torment of Mankind. He was the answer to the question, “What if none of the bad things had happened?”

Cactus Jack: The Necessary Evil

Eventually, the WWF completed the trifecta. They introduced Cactus Jack, Foley’s most violent and established persona. This persona was developed during his days in WCW, Japan, and ECW. Within the WWF narrative, Cactus was framed as the necessary evil. His personality had to be unleashed for the most brutal and dangerous situations. He was the one who could both endure and inflict the most pain. He was the hardened survivalist, the battle-scarred warrior born from a decade of wrestling wars.

The convergence of these three personas reached its ultimate expression at the 1998 Royal Rumble. Mick Foley achieved an unmatched feat of character work. He entered the 30-man Royal Rumble match three separate times. First, he appeared as Cactus Jack. Then, he entered as Mankind. Finally, he showed up as Dude Love. This moment cemented the “Three Faces of Foley” as one of the most unique and iconic gimmicks in wrestling history.

This entire arc can be read as a therapeutic journey played out on a national stage. The personas were not random. They represented distinct aspects of Foley’s life and psyche. Dude Love represented the innocent dream. Cactus Jack was the hardened survivor. Mankind showed the resulting trauma. The WWF storyline explicitly presented them as different personalities warring within one man, externalizing an internal conflict. Mankind evolved from a terrifying monster into a lovable, comedic figure. He gained a sock puppet sidekick named Mr. Socko. This change represents a narrative of healing. He began to integrate his pain with humor. He found a new way to connect with the audience that was not based solely on shared suffering. By the end of his main run, he was often billed simply as “Mick Foley, The Hardcore Legend.” This identity was singular and integrated. It absorbed the lessons and experiences of all three faces. Foley used these characters to explore the fragmented facets of himself. He examined his history. In doing so, he created a story of psychological struggle and eventual wholeness. This was unprecedented in wrestling. It resonated deeply with an audience that often felt like outcasts themselves.

Part V: The Fall That Made a Legend – Hell in a Cell

On June 28, 1998, Mick Foley, known as Mankind, stepped into a steel cage. The cage was 16 feet high and roofed. This event occurred at the King of the Ring pay-per-view in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He prepared for a Hell in a Cell match against his arch-nemesis, The Undertaker. The 17 minutes that followed would define Foley’s career. These moments would also produce the most indelible and terrifying images of the WWF’s “Attitude Era.” It was a spectacle of such brutal reality. It transcended professional wrestling and became a permanent fixture in the annals of pop culture. This was a moment where the myth of Mick Foley was forged in pain and cemented in legend.

The Setup

The match was the culmination of a two-year-long, deeply personal feud between the two characters. The first-ever Hell in a Cell match took place the previous year. It had set a high bar for violence and spectacle. In the days before the 1998 event, Foley and his mentor, Terry Funk, came up with ideas. They brainstormed on how to possibly top it. It was Funk who casually suggested, “Maybe you should let him throw you off the top of the cage”.

Foley seized upon the idea. He was concerned that the match would be underwhelming. The reason was that The Undertaker was nursing a legitimate, painful fracture in his ankle. It would limit his mobility. Foley feared a slow, plodding cage match. He believed a spectacular, shocking moment at the very beginning was necessary to make it memorable. He pitched the idea to a deeply hesitant Undertaker, who reportedly asked him, “Mick, do you want to die?”. Foley then lied to Vince McMahon. He assured the chairman he was comfortable with the stunt. He claimed he had been on top of the cage before, when in fact he had not. He later admitted that if he had climbed the structure beforehand, he would have known that getting thrown off was a terrible idea.

The First Fall

The match began in an unprecedented fashion. Mankind made his way to the ring, threw a steel chair onto the roof of the cell, and began to climb. The Undertaker followed, and the two men stood silhouetted against the arena lights, 16 feet above the ring. Moments into their brawl, The Undertaker grabbed Mankind and hurled him off the side of the cage. Foley plummeted 22 feet, crashing through the Spanish announce table below with sickening force.

The arena fell into a stunned silence, broken only by the panicked, genuine cries of commentator Jim Ross: “Good God almighty! Good God almighty! They’ve killed him!” and the immortal line, “As God as my witness, he is broken in half!”. Medical personnel, Terry Funk, and even a visibly concerned Vince McMahon rushed to Foley’s side. He had suffered a dislocated shoulder in the fall. As he was being placed on a stretcher and wheeled away, the unbelievable happened. Foley fought his way off the stretcher, a chilling smile spreading across his face, and began to walk back towards the cage. In a moment of pure, unadulterated resilience, he started to climb the cell wall again.

The Second Fall

Back on top of the cell, the brawl resumed. The Undertaker, still moving gingerly on his broken ankle, lifted Foley for a chokeslam. The plan was for the roof panel to sag under the impact, creating a dramatic visual. However, the panel was not properly secured. Instead of sagging, it gave way completely. Foley plummeted through the roof, crashing hard onto the canvas below. A steel chair that had been on the roof with them followed him down, striking him in the face and knocking him legitimately unconscious. The impact dislodged his jaw and sent one of his teeth through his lip and up into his nostril.

This second fall was entirely unplanned and far more dangerous than the first. The Undertaker, peering down through the hole in the roof, genuinely believed he had killed his friend and colleague. Jim Ross’s commentary again reflected the real-life horror of the situation: “Will somebody stop the damn match? Enough’s enough!”.

The Aftermath

Somehow, the match continued. After being revived, Foley allowed the match to reach its conclusion. In a final, gruesome act, he was chokeslammed onto a pile of hundreds of thumbtacks that he had scattered in the ring earlier, before finally being pinned by The Undertaker. He received a thunderous, sustained standing ovation from the Pittsburgh crowd.

Foley’s list of legitimate injuries from that one night was staggering: a concussion, a dislocated left shoulder, a dislocated jaw, bruised ribs, a bruised kidney, internal bleeding, puncture wounds from the thumbtacks, and several knocked-out teeth. Backstage, Vince McMahon embraced him, saying, “You have no idea how much I appreciate what you have just done for this company, but I never want to see anything like that again”. The match took a severe physical toll, and Foley has admitted that the phone call to his crying wife that night made him seriously consider retirement.

The Hell in a Cell match is a double-edged sword in Foley’s legacy. It was the moment that immortalized him, transforming him from a respected veteran into a living legend. The image of his body falling from the sky became the defining visual of the Attitude Era’s boundary-pushing excess. Signs proclaiming “Foley is God” became a common sight at arenas. However, the spectacle also threatened to overshadow the entirety of his other, more nuanced work. It created a caricature of him as purely a human crash-test dummy. This potential caricature obscured the brilliant psychological performances he had delivered in ECW. It also overlooked the development of his three personas. His career after that night can be seen as a continuous effort to live up to the fall’s legacy. At the same time, he tried to live down the memory of that terrifying and legendary moment.

Part VI: The Underdog Champion and The Odd Couple – Peak of the Mountain

After the career-defining brutality of Hell in a Cell, Mick Foley’s journey took another unexpected turn. The man had built his reputation on pain and suffering. He would reach the pinnacle of the wrestling world through humor. His vulnerability and an undeniable connection with the audience also played a role. His reign as WWF Champion was not just a commercial success. His iconic partnership with The Rock was legendary. It showcased the power of genuine heart. This happened in an era defined by attitude.

The Night the Channels Changed (January 4, 1999)

During the “Monday Night Wars,” WWF and World Championship Wrestling (WCW) engaged in a fierce television ratings battle. One of the most pivotal moments unfolded during this period. WWF’s flagship show, Raw is War, had a pre-taped episode. It was scheduled to air on January 4, 1999. Mankind was set to challenge The Rock. This match secured his first-ever WWF Championship. Because Raw was taped, WCW, which aired its show Monday Nitro live, knew the result in advance.

WCW made a competitive move that was overly ambitious. This decision would backfire spectacularly. The company instructed its lead announcer, Tony Schiavone, to spoil the result on air. Schiavone addressed the Nitro audience with dripping sarcasm. He announced that Mick Foley, “who wrestled here one time as Cactus Jack,” was going to win the WWF title. He added the now-infamous sneer, “That’ll put some butts in the seats”. The intended effect was to dissuade viewers from changing the channel. The actual effect was the exact opposite. According to television ratings data, an estimated 600,000 households immediately switched from TNT’s Nitro to the USA Network’s Raw. They wanted to witness the beloved underdog’s crowning moment.

The match itself was a perfect encapsulation of the Attitude Era’s chaotic energy. It was a no-disqualification brawl. The match featured interference from both The Rock’s villainous Corporation and their rivals, D-Generation X. The climax saw the arena erupt as the glass shattered, signaling the arrival of Stone Cold Steve Austin, who stormed the ring and blasted The Rock with a steel chair, allowing a battered Mankind to make the cover and secure the victory. The emotional outpouring from the live crowd was immense. This event is widely seen as the symbolic turning point in the Monday Night Wars. It marks the moment when the tide shifted permanently in the WWF’s favor. Compelling storytelling was more powerful than WCW’s star-studded but stagnant product. The audience deeply invested in the characters. Foley’s championship win was not just a title change; it was a victory for every fan who had followed his painful, decade-long journey. For years afterward, signs proclaiming “Mick Foley put my butt in this seat” were a staple at wrestling events.

The Rock ‘n’ Sock Connection: An Unlikely Alliance

In the latter half of 1999, Mankind and The Rock had been bitter rivals for years. However, they formed one of the most unlikely, and beloved, tag teams in wrestling history: The Rock ‘n’ Sock Connection. The formation took place on August 30, 1999. This happened when Mankind offered to help his former nemesis, The Rock. He helped fend off an attack from the colossal team of The Undertaker and Big Show.

The premise was a classic “odd couple” pairing. It featured the hilarious chemistry between The Rock’s arrogant, charismatic coolness. Mankind made goofy and earnest attempts to be his best friend. Their backstage segments became must-see television. This included the legendary “This is Your Life” segment. In it, Mankind brought out a parade of embarrassing figures from The Rock’s past. The segment drew one of the highest television ratings in Raw’s history. This success was a testament to the duo’s incredible comedic timing. It also showcased their entertainment value.

The partnership was not only entertaining but also successful. They captured the WWF Tag Team Championship on three separate occasions. This alliance was crucial for the evolution of both characters. For The Rock, it allowed him to fully transition into a top-tier fan favorite, or “babyface.” He showcased a more humorous and human side. This endeared him to the masses. For Foley, it completed Mankind’s transformation from a tortured, boiler-room-dwelling monster. He became a lovable, sock-puppet-wielding hero. This cemented his status as one of the most versatile and popular performers in the company.

In an era defined by rebellious anti-heroes, cynical aggression, and “attitude,” Mick Foley’s greatest triumphs were the complete opposite. He showcased vulnerability, earnestness, and a disarming sense of humor. The Attitude Era is often remembered for the beer-swilling rebellion of Stone Cold Steve Austin. It is also noted for the arrogant swagger of The Rock. Foley’s success, however, demonstrates a powerful counter-narrative. His championship win was not the culmination of a dominant, aggressive rampage. Instead, it was the emotional payoff to an underdog story. This story was built on years of being physically and emotionally battered. The core of his appeal was his struggle, not his strength. The success of the Rock ‘n’ Sock Connection was not based on their in-ring dominance. It was based on their entertainment value. The humor came from Mankind’s childlike, vulnerable attempts to win The Rock’s friendship. When Foley won the title, his emotional post-match celebration was heartfelt. He dedicated it to his two young children watching at home. It was a moment of pure, uncool, fatherly love. This was a radical departure from the norm. Foley gave the era a soul. It was an era often in danger of being soulless. In doing so, he became one of its biggest and most enduring stars.

Part VII: The Hardcore Legend – Author, Comedian, and Philanthropist

Mick Foley’s career did not end when his body could no longer withstand the rigors of full-time wrestling. Instead, he transitioned into a new phase of life, one that solidified his legacy as a true renaissance man. His intelligence, wit, and compassion, which had always supported his violent personas, came to the forefront. This revealed a man whose talents extended far beyond the squared circle. As an author, comedian, actor, and philanthropist, Foley shattered every stereotype associated with his profession. He left an indelible mark on popular culture.

The Bestselling Author

In 1999, Foley was at the height of his popularity. He published his first memoir, Have a Nice Day: A Tale of Blood and Sweatsocks. In a move that was virtually unheard of for a celebrity athlete, Foley wrote the entire 700-plus page book himself. He eschewed a ghostwriter. He penned the manuscript in longhand on yellow legal pads. The book was a revelation. It showcased Foley’s sharp wit, insightful storytelling, and paradoxical blend of wildness and warmth. The literary world and wrestling fans alike were captivated. Have a Nice Day shocked publishers by debuting at #1 on The New York Times Bestseller list. It remained there for 26 weeks.

This success was no fluke. He continued to write several more bestsellers. These included a follow-up memoir, Foley Is Good: And the Real World Is Faker Than Wrestling, which also hit #1. He also wrote multiple children’s books and two novels. His literary career revealed a intelligent, articulate, and thoughtful man to a mainstream audience. It shattered the “dumb wrestler” stereotype. This provided a new blueprint for how performers could brand themselves outside the ring.

The Performer: Commissioner, Comedian, Actor

Following his emotional in-ring retirement in 2000, Foley seamlessly transitioned into a new on-screen role as the WWF Commissioner. As a beloved and fair-minded authority figure, he brought a unique blend of humor and integrity to the role. He created memorable television. He proved his value as a non-wrestling performer.

In 2009, Foley embarked on yet another career: stand-up comedian and spoken-word performer. He began touring internationally with one-man shows, sharing humorous and poignant stories from his incredible life. He earned rave reviews at the world’s largest comedy festivals. These included “Just for Laughs” in Montreal and the “Edinburgh Fringe Fest” in the UK. His stage shows, much like his books, highlighted his natural warmth and wit. They connected with audiences on a deeply personal level. Foley has appeared in numerous television shows, such as 30 Rock and Boy Meets World. He was also a central, sympathetic figure in Barry Blaustein’s acclaimed 1999 wrestling documentary, Beyond the Mat.

The Philanthropist: A Heart of Gold

Perhaps the most telling aspect of Mick Foley’s character is his profound and long-standing commitment to philanthropy. He is a passionate supporter of RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network). RAINN is the largest anti-sexual violence organization in the United States. His involvement was initially inspired by his admiration for RAINN’s founder, musician Tori Amos.

Foley’s commitment went far beyond simple fundraising. He undertook the rigorous 40-hour training to become a certified volunteer for RAINN’s online crisis hotline. Over an 18-month period, he personally logged more than 550 hours on the hotline. He fielded calls and online chats from survivors of sexual assault. He offered them support and empathy in their darkest moments. He frequently auctions off his own iconic, ring-worn memorabilia. These include the boots from his last match and his signature flannel vests. He raises hundreds of thousands of dollars for RAINN. He also contributes to other charitable causes, such as the Canadian organization Mamas for Mamas. Fans, colleagues, and charity workers share anecdotes. They consistently paint a picture of a man who is exceptionally kind. He is generous and down-to-earth.

The Legacy: Hall of Famer and Hardcore Legend

Mick Foley’s decorated career, spanning multiple promotions and personas, saw him achieve remarkable success. He is a four-time world champion and an eleven-time world tag team champion across WWF/E, WCW, and ECW.

Table 1: Mick Foley’s Major Championship Reigns

| Championship | Promotion | Persona(s) | Date Won | Approximate Reign Duration |

| WWF Championship | WWF | Mankind | Dec 29, 1998 | 26 days |

| WWF Championship | WWF | Mankind | Jan 26, 1999 | 20 days |

| WWF Championship | WWF | Mankind | Aug 22, 1999 | 1 day |

| TNA World Heavyweight Championship | TNA | Mick Foley | Apr 19, 2009 | 63 days |

| WWF Hardcore Championship | WWF | Mankind | Nov 2, 1998 | 28 days (Inaugural) |

| WCW World Tag Team Championship | WCW | Cactus Jack | May 22, 1994 | 56 days |

| ECW World Tag Team Championship | ECW | Cactus Jack | Aug 27, 1994 | 70 days |

| ECW World Tag Team Championship | ECW | Cactus Jack | Dec 29, 1995 | 36 days |

| WWF Tag Team Championship | WWF | Dude Love | Jul 14, 1997 | 55 days |

| WWF Tag Team Championship | WWF | Cactus Jack | Mar 29, 1998 | 1 day |

| WWF Tag Team Championship | WWF | Mankind | Jul 13, 1998 | 13 days |

| WWF Tag Team Championship | WWF | Mankind | Aug 10, 1998 | 20 days |

| WWF Tag Team Championship | WWF | Mankind | Aug 30, 1999 | 8 days |

| WWF Tag Team Championship | WWF | Mankind | Sep 20, 1999 | 1 day |

| WWF Tag Team Championship | WWF | Mankind | Oct 12, 1999 | 6 days |

| WWF Tag Team Championship | WWF | Mankind | Nov 2, 1999 | 6 days |

| TNA Legends Championship | TNA | Mick Foley | Jul 21, 2009 | 26 days |

In 2013, his journey came full circle. Mick Foley was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame. The ceremony took place in Madison Square Garden—the very arena where his dream was born three decades earlier. Today, he serves as an official WWE Ambassador. This role recognizes his status as a respected elder statesman of the industry. He helped revolutionize this industry.

Ultimately, Mick Foley’s most profound legacy may be his complete redefinition of “toughness” in the hyper-masculine world of professional wrestling. The traditional definition was purely physical. Foley certainly met that standard, enduring a litany of horrific injuries: a ripped-off ear, second-degree burns, broken bones, a dislocated jaw, eight documented concussions (a number he admits is likely far higher), and hundreds of stitches. Yet, he expanded the definition of strength. His anti-hardcore promos in ECW demonstrated intellectual toughness—the courage to stand against a hostile crowd and critique them from a place of artistic principle. His Mankind interviews with Jim Ross showed emotional toughness—the courage to publicly explore his own insecurities and traumas on national television, laying his soul bare for millions. His tireless work with RAINN reveals a profound moral toughness—the courage to confront the deeply uncomfortable subject of sexual violence and dedicate hundreds of hours to empowering survivors, a task many would find emotionally overwhelming. And his success as a comedic, lovable character showed a different kind of bravery—the courage to be silly, vulnerable, and goofy in a world that prizes intimidating machismo.

Foley created a new, more holistic archetype for a wrestling hero. He proved that a man could be thrown off a 22-foot cage and write a children’s book. A man could bleed for a living and cry on a crisis hotline. He could be a “Hardcore Legend” and a loving, doting father. He did not just put his body on the line; he put his whole, authentic self on the line. This is why Mick Foley is one of the most beloved figures in the history of the business. He is respected and important.

Leave a comment