*Warning: In Section V: The Darkest Days: A Franchise in Freefall (The 1980s) subsection A Toxic Culture there is a brief mention of sexual assaults that happened under his Ownership at Maple Leaf Gardens. If you or someone you know is a victim of a sexual assault, please contact your local police department. Report the incident to them. Resources are also available at sexualviolencehelpline.ca and there is also a 24/7 support centre line at 1-877-392-7583.

I. Introduction: A Tale of Two Dynasties – The Glory and the Ruin

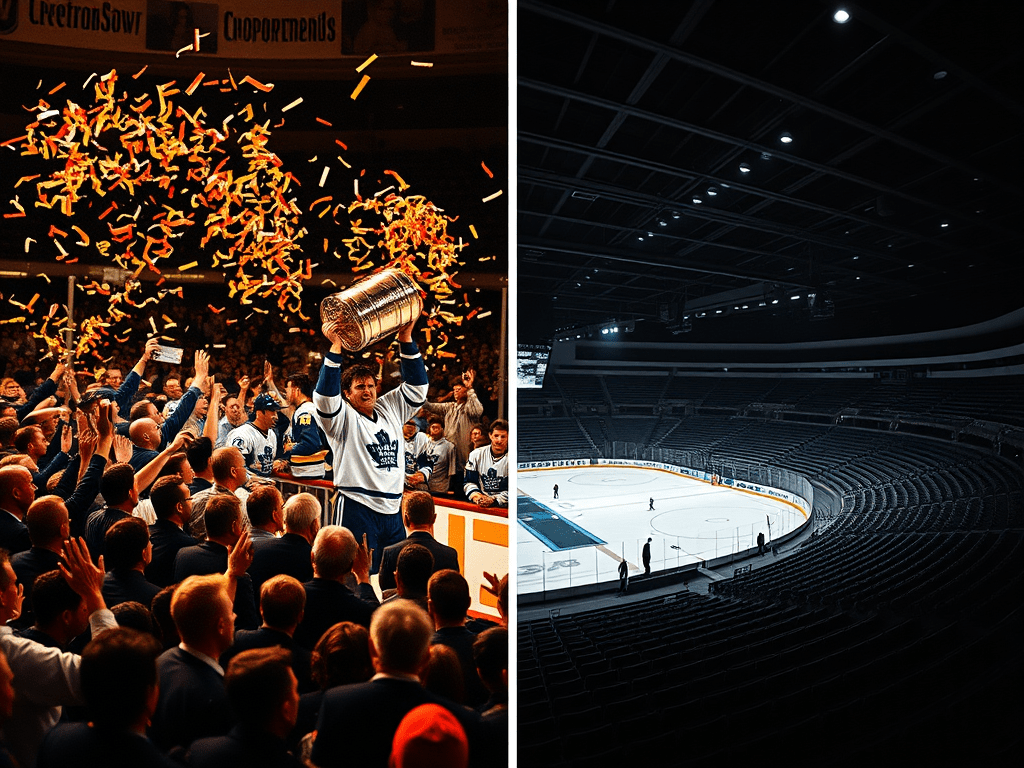

In the spring of 1967, the Toronto Maple Leafs were improbable, aging, yet ultimately triumphant Stanley Cup champions. They stood atop the hockey world for the fourth time in six seasons. This achievement was a testament to their veteran guile and championship pedigree. A key figure in the ownership box, a partner in this celebrated dynasty, was a shrewd businessman named Harold Ballard. The moment represented the pinnacle of an era for one of the National Hockey League’s most storied franchises.

Fast forward to the 1980s, and the portrait could not be more different. The proud Maple Leafs had devolved into a perennial loser. The team was so mismanaged and chaotic that it became widely regarded as the “laughingstock of the league”. The organization was a circus. Its star players were alienated or exiled. The fan base, one of the most loyal in all of sports, had been stripped of all hope. They were conditioned to expect nothing but failure and disappointment. The common denominator between the glory and the ruin was Harold Ballard.

Harold Ballard’s 18-year reign as principal owner started in 1972 with his consolidation of power. This period lasted until his death in 1990. It was not merely a period of cyclical decline. The dismantling of a proud franchise was systematic and deliberate. A toxic combination of avarice, ego, and vindictiveness drove it. His tenure serves as one of the most stark cautionary tales in the history of professional sports ownership. This report will analyze how Ballard’s personal character influenced specific actions. These actions showed how his management philosophy created deep damage to the team’s on-ice performance. It also harmed its organizational culture and public reputation. Furthermore, it will detail the monumental effort required to begin the recovery process after his death. Starting the recovery was a long and arduous process. Its effects still echo through the franchise today.

II. The Ascent: From Partner in Glory to Autocratic Ruler (1930-1972)

Harold Ballard’s eventual iron-fisted control of the Toronto Maple Leafs did not happen by chance. It was the result of a decades-long, calculated pursuit of power. His journey began as a sports-obsessed businessman. He became the sole, autocratic ruler of Maple Leaf Gardens through shrewd opportunism. He used financial leverage and had a knack for capitalizing on the misfortunes of his partners.

Early Ambitions and Rise (1930s-1950s)

Edwin Harold Ballard was born in 1903 as the only child of a successful machinist and businessman. He enjoyed a privileged upbringing. This privilege allowed him to pursue a “playboy lifestyle” even during the Great Depression. His passion for sports was evident early on. He competed as a speed skater. He also raced hydroplane boats. Additionally, he managed amateur hockey teams. His initial forays into hockey management with the Toronto National Sea Fleas in the 1930s signaled future achievements. After a player mutiny against his coaching style, he arranged a European tour to salvage the season. This episode included his arrest in a Paris restaurant. His team ended up being the first Canadian squad to fail to win gold at a World Championship.

His ambition, however, was always fixed on the city’s premier hockey club. In 1940, his connection to Leafs star Hap Day helped him become president of the Toronto Marlboros. The Marlboros were the Maple Leafs’ junior and senior affiliate teams. This was his crucial entry point into the organization he would one day dominate. He successfully ran the Marlboros for years. During this tenure, he fostered a key friendship with Stafford Smythe, son of the Leafs’ patriarchal owner, Conn Smythe. In 1957, an aging Conn Smythe stepped back from day-to-day operations. He turned control over to a seven-person committee headed by Stafford. Within months, Ballard was appointed to the committee. It was known as the “Silver Seven.” This appointment officially marked his arrival in the Maple Leafs’ senior management structure.

The Triumvirate and the Glory Years (1961-1968)

The pivotal moment came in November 1961. Conn Smythe sold the majority of his shares in Maple Leaf Gardens Ltd. to a consortium formed by his son Stafford, newspaper publisher John Bassett, and Harold Ballard. The deal was made possible by Ballard’s financial muscle; he fronted Stafford Smythe most of the $2.3 million purchase price, a fact that gave him immense leverage over his partner from the outset.

During the subsequent years, the team experienced a renaissance on the ice, winning four Stanley Cups between 1962 and 1967. In this successful triumvirate, Ballard’s primary role was not hockey operations but maximizing the profitability of Maple Leaf Gardens. He proved to be a master promoter, booking a wide array of non-hockey events and implementing aggressive marketing strategies. Within three years, profits at the Gardens had tripled to nearly $1 million. This period, however, also offered the first clear glimpses of the imperious and abrasive personality that would later define him. He famously took down a large portrait of Queen Elizabeth II from the arena’s end wall. This allowed him to make room for more seating. He quipped, “She doesn’t pay me, I pay her”. In another incident, when the CBC balked at paying for a new lighting system required for color television, Ballard reportedly grabbed a fireman’s axe and threatened to sever the broadcast cable minutes before a game unless the network paid up.

The Coup d’État (1969-1972)

The partnership began to fracture in 1969, a turning point that set the stage for Ballard’s ultimate takeover. An RCMP investigation led to charges against Ballard and Stafford Smythe for multiple counts of tax evasion and fraud. They were accused of using over $200,000 in Maple Leaf Gardens funds for personal expenses. These expenses included home renovations and motorcycles for their sons. This was the first concrete evidence of Ballard’s operating principle: the organization’s assets were his personal piggy bank.

John Bassett, then chairman of the board, took decisive action due to the scandal. He orchestrated a vote to fire both Ballard and Smythe from their management posts. However, in what would prove to be a monumental strategic error, Bassett did not force them to sell their shares. As the largest shareholders, Ballard and Smythe remained on the board, controlling nearly half the company’s stock. A year later, they used their position to stage a proxy war. They successfully regained control of the board. They ousted Bassett and bought him out in September 1971.

The final piece fell into place with shocking speed. Just six weeks after their victory over Bassett, Stafford Smythe died from complications of a bleeding ulcer. At 68 years old, Ballard saw his moment. He fought with Smythe’s family. He went into debt to purchase their shares. This move consolidated a controlling interest of between 60% and 71% of Maple Leaf Gardens Ltd.. By February 1972, the coup was complete. Harold Ballard became the president and chairman. He was the undisputed, sole ruler of the Toronto Maple Leafs. He also ruled their iconic arena. His long strategy was successful. The partnership had served merely as a means to an end. That end was absolute power.

III. The “Carlton Street Cashbox”: Profit Before Pride, Money Before Mates

Once Harold Ballard seized absolute control, the Toronto Maple Leafs organization underwent a fundamental philosophical transformation. The pursuit of championships, the hallmark of the Conn Smythe and early triumvirate years, was immediately set aside. The focus shifted to the relentless pursuit of profit. Maple Leaf Gardens was once a cathedral of hockey. It was converted into the “Carlton Street Cashbox.” The team itself became little more than a loss leader for a far more lucrative entertainment business. Ballard’s financial strategy focused on parasitic extraction. He leveraged the unwavering loyalty of a captive fanbase. This created a high-profit, low-investment enterprise. It would ultimately hollow out the franchise from the inside.

The Ballard Doctrine: Victory is Optional, Profit is Mandatory

Ballard quickly surmised a core economic truth about his new asset. In Toronto, the Maple Leafs were a guaranteed sell-out. This was true regardless of the quality of the on-ice product. This realization formed the bedrock of his ownership doctrine. Fans would fill the building to watch a losing team. Therefore, he believed there was no need to spend money on star players. Investing in top-tier coaching was also seen as an unnecessary and foolish expense. Modern scouting was not considered essential either. He ran the franchise like a “small mom-and-pop organization.” He micromanaged every detail. His focus was solely on the bottom line. This management style was profoundly detrimental to the team. The hockey club essentially became a tenant in its own building. Its needs and ambitions were secondary to the arena’s financial performance.

A Masterclass in Miserliness

This philosophy manifested in a legendary stinginess that permeated every corner of the organization. The rival World Hockey Association (WHA) emerged in 1972. It created a competitive market for player salaries for the first time. However, Ballard steadfastly refused to engage. His refusal to pay market rates was hardline. This resulted in an immediate and devastating exodus of talent. Players like goaltender Bernie Parent departed for the higher pay offered by the new league. This wasn’t just being frugal; it was a conscious decision to sacrifice competitiveness for cash.

His cheapness became the stuff of legend, often descending into the absurd. The NHL mandated that player names be added to the back of jerseys. Ballard resisted the mandate. He claimed it would hurt sales of his $2.50 game programs. When the league began fining him $2,000 per day, he complied maliciously. He had the names stitched in letters that were the same color as the jersey fabric. This made them invisible to fans in the stands. He was known to fine players for on-ice infractions and even made them pay for their own equipment. Star forward Rick Vaive scored 50 goals for the third consecutive season. This was an elite accomplishment. Despite this, Ballard still refused to give him a raise. He reportedly told him, “If you think you’re getting another F-ing dime out of me, you’re crazy”.

The Criminal Owner and the Tarnished Brand

Ballard’s view of the organization’s finances as his personal property was not just a management philosophy. It was a criminal one. Shortly after taking control in August 1972, he faced legal repercussions. He was convicted on 47 of 49 counts of fraud, theft, and tax evasion. The court found a “clear pattern of fraud” involving the misuse of $205,000 of Maple Leaf Gardens Ltd. funds to pay for personal expenses. These included renovations on his home and cottage. Additionally, he spent money on limousine rentals for his daughter’s wedding and motorcycles for his sons. These motorcycles were brazenly passed off as hockey equipment for the Marlboros.

He was sentenced to three consecutive three-year terms but served only one year at the medium-security Millhaven Institution. Upon his release, he showed no remorse. He expressed disdain for the justice system. He boasted that prison was “like staying in a motel, with colour television, golf, and steak dinners”. This episode forever stained the reputation of the franchise. For nearly two decades, a convicted and unrepentant criminal led one of Canada’s most cherished sporting institutions. This fact eroded the team’s public image. It also harmed its moral standing.

The Arena as a Personal Fiefdom

While the hockey team withered from neglect, Maple Leaf Gardens flourished under Ballard’s predatory genius. He was a peerless promoter. He booked the arena with a constant stream of high-grossing events. These included rock concerts featuring The Beatles and Elvis Presley, religious revivals, and the famous 1966 Muhammad Ali vs. George Chuvalo boxing match. He understood that if there was money to be made, it didn’t matter who was performing on stage. The players in the rink were irrelevant.

His methods for extracting every last dollar were ruthless. During a Beatles concert on a hot summer day, he allegedly ordered the building’s heat to be turned up. He had the public water fountains shut off. He instructed concession stands to sell only large, overpriced drinks. As a result, he made a fortune on beverage sales. The line between the public institution and his private domain completely dissolved. He built himself a lavish apartment, known as the “bunker,” inside the Gardens. He began living there after his wife’s death. He treated the arena and the team as his personal fiefdom, accountable to no one but himself.

IV. A Reign of Error: Deconstructing a Dynasty, Player by Player

Harold Ballard’s most destructive legacy was his systematic dismantling of the team’s human capital. His management of players was not guided by hockey sense or business acumen. Instead, it was driven by personal whims. It was motivated by petty grievances. He had an insatiable need to be the sole star of the show. He treated players not as valuable assets but as disposable subjects. Any perceived challenge to his absolute authority came from a captain seeking a fair contract. It could also come from a star player with popular support or a coach earning the team’s respect. Each was met with public humiliation. They faced vindictive retribution and eventual expulsion. This war on his own talent was the primary catalyst for the team’s on-ice collapse.

Case Study 1: The Humiliation of Dave Keon (1972-1975)

No single episode better encapsulates Ballard’s destructive ego than his treatment of Dave Keon. Keon exemplified the Maple Leafs’ glory years. He was a four-time Stanley Cup champion. He also won the 1967 Conn Smythe Trophy as playoff MVP and served as the team’s respected captain. After a statistically poor season in 1974-75, Ballard publicly criticized his leadership. He refused to grant him a pay raise. He also denied him the no-trade clause he had previously enjoyed.

When Keon’s contract expired, Ballard made it clear there was no place for him on the team. However, instead of trading him, Ballard engaged in an act of pure malice. He told the 35-year-old Keon he could make his own deal with another NHL team. Then he set the required compensation price—reportedly a first-round draft pick—so prohibitively high that no team would meet it. In effect, he blocked one of the franchise’s greatest icons from playing anywhere in the NHL. This act was not about maximizing asset value; it was about power and punishment.

Forced out of the league he had starred in for 15 seasons, Keon reluctantly jumped to the rival WHA. The bitter feud created a deep wound that festered for decades. Keon refused any association with the Leafs organization. He turned down invitations to the closing ceremony of Maple Leaf Gardens in 1999. He also rejected a proposal to honor his number. The estrangement between the franchise and its greatest living player was a potent cultural symbol. It showed the damage inflicted by Ballard. The rift did not begin to heal until a new generation of management took over, long after Ballard was gone.

Case Study 2: The Spite Trade of Lanny McDonald (1979)

By the late 1970s, the Leafs had assembled a promising young core. It featured players like Börje Salming and Mike Palmateer. Two stars were immensely popular with the fans: captain Darryl Sittler and the mustachioed, high-scoring winger Lanny McDonald. This promising core was shattered by another of Ballard’s ego-driven decisions. In 1979, Ballard hired Punch Imlach as general manager. Imlach was equally autocratic. He shared Ballard’s animosity towards the burgeoning NHL Players’ Association. Its influential executive director was Alan Eagleson (also a criminal), who also happened to be Sittler’s agent.

Imlach immediately clashed with Sittler. He wanted to trade him. However, the captain had a no-trade clause in his contract. Sittler refused to waive it. Imlach and Ballard were unable to move the captain. They chose the next most painful option. They decided to punish Sittler by trading his best friend and linemate. On December 28, 1979, they shocked the hockey world. In a move that had no hockey logic, they dealt Lanny McDonald to the miserable Colorado Rockies. McDonald was devastated by the trade. The trade, which McDonald later described as an act of “vindictiveness,” sent shockwaves through the city. Outraged fans picketed outside Maple Leaf Gardens in protest, but the damage was done. The management sacrificed a future Hall of Famer. He was one of the team’s most beloved players.

Case Study 3: The Expulsion of Darryl Sittler (1979-1982)

The McDonald trade was the final straw for Darryl Sittler. Before the next game, in a dramatic and symbolic act of protest, he took a pair of scissors. He physically cut the captain’s ‘C’ from his jersey. This act signified that he could no longer lead a team under such management. While Imlach was hospitalized with a heart attack, a temporary and uneasy truce was brokered the following season. However, the relationship between Sittler and Ballard was irrevocably broken.

The conflict continued for a while. Sittler became weary of the toxic environment. Finally, he informed management he would waive his no-trade clause. In 1982, he was traded to the Philadelphia Flyers, completing Ballard’s purge of the team’s leadership and soul. Within a few short years, Ballard had driven away two captains. He also drove away a fan-favorite Hall of Famer. It was all in the service of his own ego.

The Coaching Carousel

Ballard’s intolerance for any authority but his own extended to the bench. He churned through coaches with astonishing frequency, creating an environment of instability where no long-term strategy could ever take root. During his 18 years of sole ownership, he made 11 coaching changes. This ensured that no coach could ever build the rapport with players or the media. Such a rapport might threaten Ballard’s position as the center of attention.

The most notorious incident involved Roger Neilson, a respected and innovative coach hired in 1977. Neilson was dubbed “Captain Video” for his pioneering use of videotape to analyze games. He quickly earned the players’ respect. In 1978, he led the team to the Stanley Cup semifinals. This success seemed only to fuel Ballard’s envy. In March 1979, he abruptly fired Neilson, but when he couldn’t secure a replacement, he was forced to rehire him. The situation turned into an utter farce. Ballard attempted to humiliate the coach in a bizarre manner. He tried to convince Neilson to wear a paper bag over his head. This was for his return to the bench. Neilson, to his credit, refused. The episode turned the once-proud Maple Leafs into a national punchline.

Table: The Talent Drain (1972-1990)

The following table starkly illustrates the volume of elite talent. Much of this talent was driven out of Toronto. Some of it was lost due to Ballard’s mismanagement.

| Player Name | Years with Leafs | Key Accomplishments with Leafs | Year of Departure | Reason for Departure | Subsequent Career Highlights |

| Bernie Parent | 1970-1972 | Promising young goaltender | 1972 | Jumped to WHA after salary dispute | Returned to NHL with Flyers, won 2 Stanley Cups, 2 Conn Smythe Trophies, 2 Vezina Trophies, Hall of Fame |

| Dave Keon | 1960-1975 | Captain, 4 Stanley Cups, 1967 Conn Smythe Trophy, franchise icon | 1975 | Forced to WHA after bitter contract dispute and public humiliation by Ballard | Played 6 seasons in WHA/NHL, decades-long estrangement from Leafs |

| Lanny McDonald | 1973-1979 | 3x 40-goal scorer, fan favorite | 1979 | Traded to Colorado out of spite to punish Darryl Sittler | 66-goal season with Calgary, won 1989 Stanley Cup as Flames captain, Hall of Fame |

| Darryl Sittler | 1970-1982 | Captain, franchise all-time leading scorer at time of departure, 10-point game | 1982 | Demanded trade after years of conflict with Ballard/Imlach | Continued productive career with Flyers and Red Wings, Hall of Fame |

| Ian Turnbull | 1973-1981 | Offensive defenseman, holds NHL record for goals by a defenseman in one game (5) | 1981 | Traded after clashing with management | Played parts of two more NHL seasons |

| Rick Vaive | 1980-1987 | Captain, first 50-goal scorer in team history (3x) | 1987 | Traded after public contract disputes and being stripped of captaincy | Scored 43 goals in his first season after trade |

V. The Darkest Days: A Franchise in Freefall (The 1980s)

The cumulative effect of Ballard’s reign of error was a complete collapse on the ice. Financial neglect harmed the team. There was a war on star players. Coaching instability further exacerbated the situation. The 1980s, his lone full decade of proprietorship, represented the absolute nadir in the modern history of the franchise. The on-ice failure, however, was merely a symptom of a deeper disease. A cultural and moral rot started at the very top. It permeated the entire organization, turning a revered institution into a national disgrace.

Statistical Anarchy

The numbers from the Ballard era tell an unambiguous story of decline. During Ballard’s sole ownership from February 1972, the Maple Leafs struggled in the regular season. This period lasted until his death in April 1990. This record consisted of 596 wins, 736 losses, and 207 ties. In those 18-plus seasons, the team managed only six winning campaigns. They never once finished higher than third in their division. In his final 13 seasons at the helm, they won a grand total of two playoff series (sounds familiar).

The 1980s were particularly bleak. The decade produced some of the worst teams in franchise history. This included a dreadful 1984-85 campaign. During this time, the team won just 20 of 80 games and finished with a mere 48 points. The team’s goal differential during this period was catastrophic, reaching a low of -105 in 1984-85. The team suffered this statistical freefall because the owner gutted his team of talent. He refused to invest in its future.

Table: A Tale of Two Eras – On-Ice Performance

The contrast between the team’s performance with Ballard as a part-owner and his record as sole owner is clear. It provides irrefutable evidence of his destructive impact.

| Metric | Pre-Sole Ownership (1961-62 to 1971-72) | Ballard’s Sole Ownership (1972-73 to 1989-90) |

| Total Seasons | 11 | 18 |

| Winning Seasons | 9 | 6 |

| Losing Seasons | 2 | 12 |

| Playoff Appearances | 9 | 13 |

| Playoff Series Wins | 8 | 4 (only 2 after 1978) |

| Stanley Cup Finals Appearances | 4 | 0 |

| Stanley Cup Championships | 4 | 0 |

A Toxic Culture

The organization’s character and public image collapsed along with the on-ice ineptitude. This collapse was shaped entirely by Ballard’s own persona. He was infamous for his crude, offensive, and often bigoted public statements. He openly disparaged women. He told a CBC Radio host that “they shouldn’t let females on the radio anyway, they’re a joke”. His racism and xenophobia were also well-documented. He was disgusted by the signing of European players like Börje Salming. He was known to use vile racial slurs when referring to Black players. This behavior came directly from the owner’s office. It transformed the Maple Leafs’ brand from one of civic pride to one of public embarrassment.

The most disturbing manifestation of the cultural decay under Ballard was the sexual abuse scandal. This scandal took place within the walls of Maple Leaf Gardens. For years, a pedophile ring operated out of the arena. Employees like Gordon Stuckless and John Paul Roby preyed on young boys. These boys were drawn to the building by their love for the Leafs. The abuse was described as “common knowledge among the staff”. While there has never been any legal proof that Ballard was directly involved, multiple victims alleged that he was aware of the abuse and did nothing to stop it. One victim even alleged that Ballard himself solicited him for a sex act and had him thrown out of the arena when he refused.

Former player and coach Red Kelly witnessed the transition from the previous ownership. He captured the essence of the change. He stated that under Ballard, “it was as if a bunch of pirates had taken over”. This “pirate” atmosphere, devoid of accountability, professionalism, and basic morality, created the conditions where such horrific crimes could occur. The losing records reflected poor performance. The moral scandals revealed deeper issues. Both stemmed directly from an owner who cared for nothing beyond his own gratification.

VI. The Long Road Back: Rebuilding from the Ashes (1990-1994)

The death of Harold Ballard on April 11, 1990, did not bring immediate salvation to the Toronto Maple Leafs. It did not resolve the issues plaguing the team. Instead, it revealed the true depth of the wreckage he had left behind. It also triggered a chaotic power struggle for the soul of the franchise. The subsequent recovery, though remarkably swift, required a complete philosophical reversal of everything the Ballard era stood for. The team’s rapid resurgence in the early 1990s serves as the ultimate indictment of Ballard’s reign. It proves that the “curse” that had plagued the team was not supernatural. Instead, it was a man-made affliction of incompetence and neglect.

The Inheritance: A Franchise in Ruins (1990)

The franchise Ballard left behind was a smoldering ruin. The 1990-91 season was the first full campaign after his death. The team hit rock bottom. They finished last in the Norris Division with a pathetic 23-46-11 record for just 57 points. The roster was a shell of its former self, depleted of high-end talent and led by a young Vincent Damphousse. Years of neglecting the draft and trading away picks had left the farm system barren. One year, Ballard reportedly instructed his scouts to draft players from nearby Belleville. He did this simply because he didn’t want to spend money on a proper scouting department.

The public image was that of a joke franchise, a once-proud organization haunted by two decades of buffoonery and failure. Fans had lost all trust and hope. Many believed the team was afflicted by a “Ballard Curse”. They thought it doomed the team to perpetual mediocrity.

The Power Struggle and a New Beginning

Ballard’s death at age 86 ignited a bitter and public battle for control of his vast empire. His empire was valued at over $100 million. It included the team, the arena, and a printing company. The fight pitted his three estranged children against his longtime companion, Yolanda Ballard. His will was complex and controversial, much like the man himself. It left control of his holding company to a three-man trust. This trust could not exceed 21 years. Eventually, the proceeds were destined for a charitable foundation.

From this legal and financial chaos, a new leader emerged: supermarket tycoon Steve Stavro. Stavro was a longtime friend and business associate of Ballard’s. He was also one of the executors of his will. Stavro navigated the complex battle for control. By 1991, he had secured the backing of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan. He gained control of the team. This change ushered in a new era of ownership. Stavro’s approach was the polar opposite of his predecessor’s. He hated the limelight. He rarely interfered in hockey operations. He understood the need to invest in professional management.

The Fletcher-Burns Revolution

Stavro’s first decision was critical. He chose to hire a proven hockey architect. Stavro provided him with the resources and autonomy to rebuild. In 1991, he hired Cliff Fletcher. Fletcher was the highly respected general manager who had built the Calgary Flames into a Stanley Cup champion. Fletcher’s philosophy was the antithesis of Ballard’s. He was aggressive, willing to make bold trades, and understood that talent acquisition was the key to winning. He immediately hired a tough, no-nonsense coach in Pat Burns, who had enjoyed success with the rival Montreal Canadiens.

Fletcher’s signature move came on January 2, 1992. This remains one of the largest trades in NHL history. He engineered a massive 10-player deal with his former team, the Calgary Flames. The centerpiece of the trade was acquiring fiery, skilled center Doug Gilmour. This single transaction instantly changed the identity and trajectory of the franchise. Fletcher continued to build. He acquired powerful winger Dave Andreychuk from Buffalo. He also promoted a talented young goaltender from the draft class of 1990, Felix Potvin.

The Resurgence and Restoration of Hope (1992-1994)

The results were immediate and spectacular. In the 1992-93 season, the rebuilt Maple Leafs stunned the hockey world. This happened just two years after finishing with 57 points. Gilmour’s franchise-record 127 points powered them. They finished with a then-franchise-record 99 points. They then embarked on a thrilling playoff run. They dispatched the Detroit Red Wings and St. Louis Blues in dramatic seven-game series. They came within a single victory—and a controversial non-call on a Wayne Gretzky high stick—of reaching the Stanley Cup Final.

The team proved it was no fluke. They followed up with another strong season. The team made a trip to the conference finals in 1993-94. While neither of these seasons ended with a championship, their importance cannot be overstated. They exorcised the demons of the Ballard era. For the first time in two decades, the Maple Leafs were not a joke; they were a contender. Pride and dignity had been restored to a city. Most importantly, hope had been returned to a fanbase that had been starved of it for far too long. The rapid turnaround was definitive proof. The team’s problems were never about a curse or a hex. They were about the man who had deliberately held it down for so long.

VII. Conclusion: The Lingering Shadow and Lessons of a Tyrant’s Reign

The legacy of Harold Ballard’s ownership is a deep and enduring scar on the history of the Toronto Maple Leafs. His 18-year tenure as the franchise’s sole proprietor did not represent simple misfortune. Instead, it was a comprehensive deconstruction of a sporting institution. The damage he inflicted was multifaceted. A generation of Hall of Fame talent was squandered or driven away. Two decades were lost to on-ice futility and organizational chaos. The club’s moral compass was shattered, culminating in the horrific sexual abuse scandal that unfolded under his watch. A Stanley Cup drought that began during his co-ownership in 1967 became an entrenched reality under his sole, destructive leadership.

Perhaps the most insidious and lasting damage was psychological. The Ballard years conditioned a generation of Leafs fans to expect, and even accept, failure. It fostered a deep-seated pessimism. Fans developed a sense of fatalism that the team was somehow cursed. They believed any glimmer of hope would inevitably be extinguished by incompetence or malice. The trust between the fans and the organization was fundamentally broken. Ballard exploited their loyalty. He knew they would fill the building no matter how poor the product was. By doing so, he poisoned the well of goodwill. Goodwill is the lifeblood of any sports team. Cliff Fletcher and Steve Stavro revived the team’s fortunes with remarkable speed in the early 1990s. This revival was crucial in beginning to heal this wound. However, the psychological scars of the Ballard era arguably still surface in the collective anxiety of the fanbase today.

Ultimately, Harold Ballard’s reign stands as the consummate cautionary tale in professional sports ownership. It starkly demonstrates how a single individual’s character flaws can corrupt and nearly destroy a franchise. In his case, it was a toxic brew of greed, megalomania, and vindictiveness. This combination affected even a storied, financially powerful, and passionately supported franchise. He was an undeniable master at turning Maple Leaf Gardens into a profit center. His legacy for the hockey team is profound. It has left generational damage. The modern, corporate structure of Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment is a direct reaction to the chaotic circus he created. This structure is necessary in many ways.

The story of the Harold Ballard era is therefore more than just a chronicle of a bad owner. It is a study in the erosion of institutional integrity. It serves as a warning about the dangers of unchecked power. It is also a testament to the remarkable resilience of a fanbase whose loyalty was abused but never fully extinguished. The long, dark shadow he cast over the franchise is a permanent and indelible part of its history. It represents a chapter that makes the ongoing, multi-generational quest for another Stanley Cup not just a sporting goal. It is a long-overdue redemption.

Leave a comment